Pompeii Miscellaneous.

Danish Artists The Grand Tour Bronze Foundries Hotels, Local Houses, Railways Pompeii Guides Tickets Mysteries to solve Maledizione – Curse of Pompeii

Danish

Artists

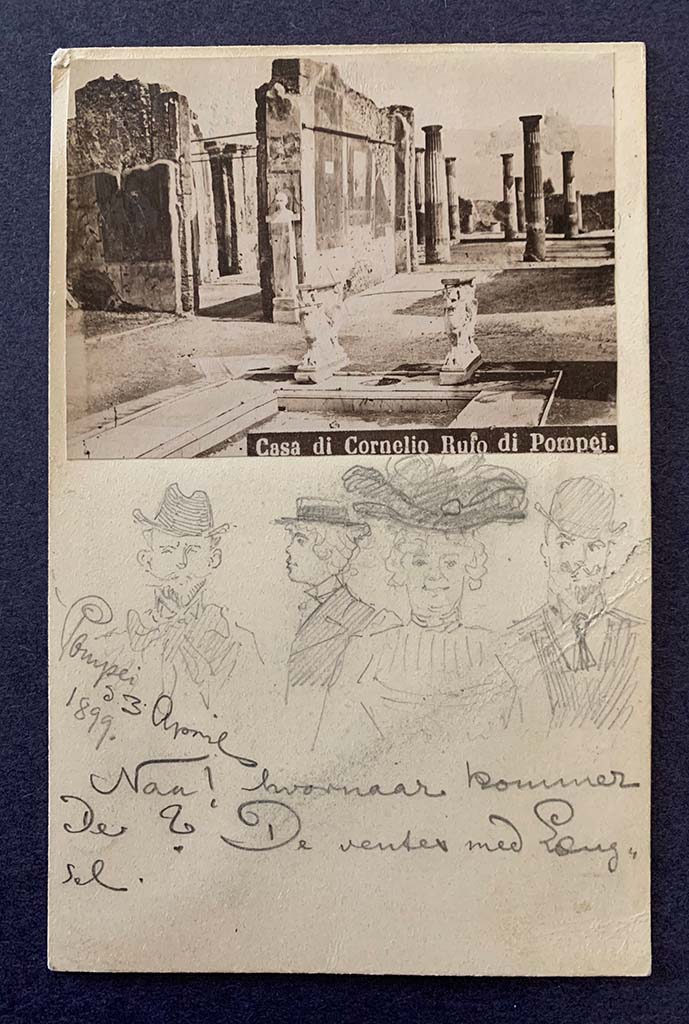

VIII.4.15

Pompeii. Postcard with drawing of four people dated 3rd April 1899.

The

message in Danish under the drawing appears to say When will you come? They

waited long in the sun.

Photo

courtesy of Rick Bauer.

VIII.4.15

Pompeii. Front of 1899 postcard. It is addressed to J. Filseth, Redaktor, in

Rome.

This

could be Johan Filseth (born 25 September 1862 in Romedal, Norway, died 5

September 1927 in Denmark).

Filseth

was the founder, in 1894, and long-time editor of the newspaper Gudbrandsdølen

in Lillehammer.

He was

connected to Denmark through his wife, a Danish woman, Laura Anna Emilie Krabbe

(1879-1969) who he married in 1900.

Photo

courtesy of Rick Bauer.

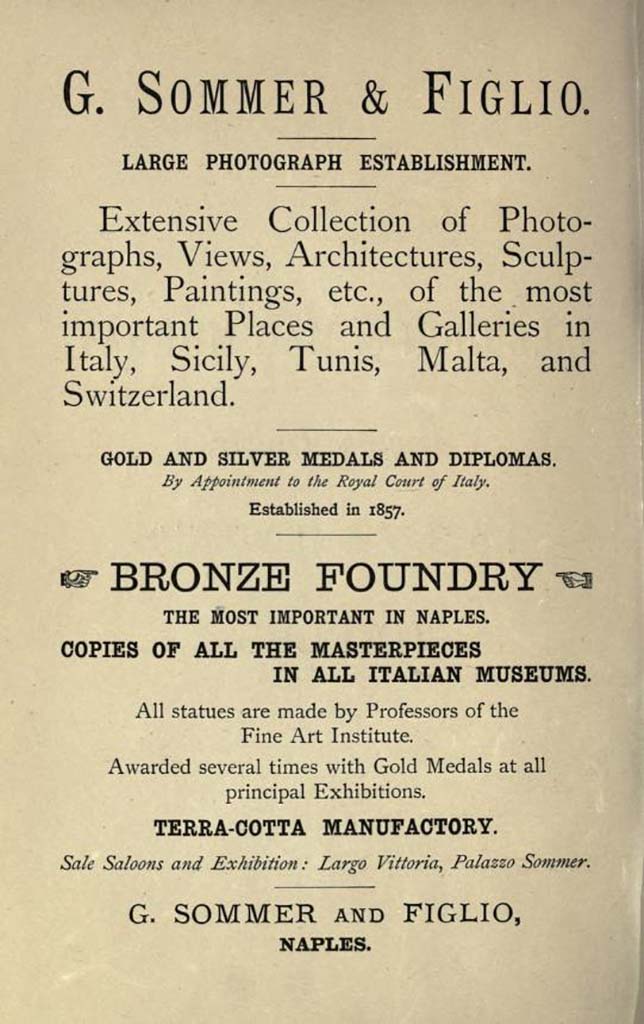

VIII.4.15

Pompeii. Note on the side of the front of the 1899 postcard which appears to

identify the people in the drawing.

The

phrase on the left-hand side of the address side “Billedhugger Gyde Petersen

og Frue” translates as “The sculptor Gyde Petersen and wife”.

Hans

Gyde-Petersen was baptised 26th December 1862 as Hans Gyde Pedersen

but later changed his name to Hans Gyde-Petersen.

His

sculpture won him a grant to study in Italy from 1897 to 1899.

During

these years in Italy, he turned his back on a promising career as a sculptor

and returned to his first love of landscape painting.

He was

part of the Skagen artists group on the northern tip of Denmark.

He was

knighted by the Danish King in 1910.

He died

in Denmark in 1943.

Underneath

is what looks like: "Maleren Viggo Langer og Frue” (the painter

Viggo Langer and wife).

Viggo

Langer was a Danish artist.

Born

Viggo Hansen on Nov. 11th 1860 in Reudnitz (by Leipzig, Germany), died Oct.11

1942 in Rungsted, Denmark.

His

father was Danish and moved the family back to Copenhagen in 1864.

He adopted his mother's family name Langer in 1885 to

avoid confusion with another painter, an artist known as Viggo Hansen.

There is

a painting of his titled “Evening scene in Pompeii” on which is the date 1899

which would fit with this postcard.

Who drew

the sketch is unknown but possibly it was another Danish artist who was in

Italy in 1899.

The Grand Tour

The Grand Tour of the late 17th, 18th and 19th centuries saw many upper class, wealthy and aristocratic gentlemen travel to Italy and Europe for pleasure, education and inspiration.

This afforded them the opportunity to view important classical and Renaissance works of art and architecture.

Many Grand tourists collected souvenirs in the form of bronze and marble models of sculpture and architecture and formed collections of Grand Tour objects for their English country houses.

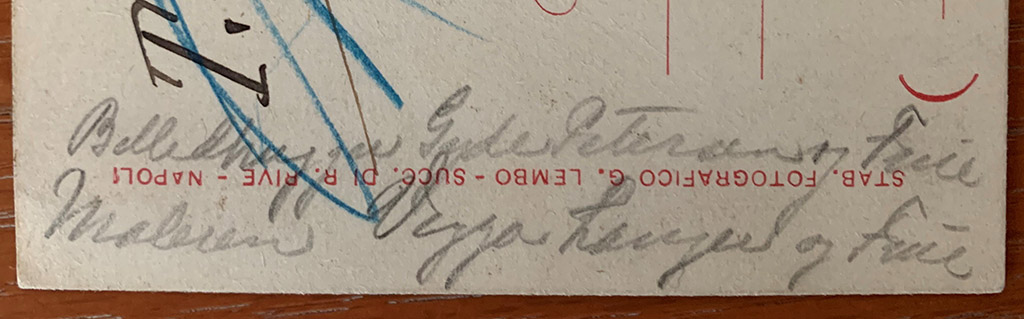

The term ‘Grand Tour’ was coined by the Catholic priest and travel writer Richard Lassels (also Lascelles) (circa 1603-68), in his influential guidebook The Voyage of Italy, or a Compleat Journey through Italy, published in Partis in 1670, to describe young lords travelling abroad to learn about art, architecture and antiquity.

Lassels was a tutor to several of the English nobility and travelled through Italy five times.

In his book, he asserts that any truly serious student of architecture, antiquity, and the arts must travel through France and Italy, and suggested that all "young lords" make what he referred to as the Grand Tour in order to understand the political, social, and economic realities of the world.

Pompeii and Herculaneum, after their discovery, became part of this tour.

See Lassels R The Voyage of Italy - Getty Digitised Version on Archive.org

The Grand Tour offered a liberal education, and the opportunity to acquire things otherwise unavailable, lending an air of accomplishment and prestige to the traveller. Grand Tourists would return with crates full of books, works of art, scientific instruments, and cultural artefacts – from snuff boxes and paperweights to altars, fountains, and statuary – to be displayed in libraries, cabinets, gardens, drawing rooms, and galleries built for that purpose. The trappings of the Grand Tour, especially portraits of the traveller painted in continental settings, became the obligatory emblems of worldliness, gravitas and influence. Artists who particularly thrived on the Grand Tour market included Carlo Maratti, who was first patronised by John Evelyn as early as 1645, Pompeo Batoni the portraitist, and the vedutisti such as Canaletto, Pannini and Guardi. The less well-off could return with an album of Piranesi etchings.

In Rome, antiquaries like Thomas Jenkins were also dealers and were able to sell and advise on the purchase of marbles; their price would rise if it were known that the Tourists were interested. Coins and medals, which formed more portable souvenirs and a respected gentleman's guide to ancient history were also popular. Pompeo Batoni made a career of painting the English milordi posed with graceful ease among Roman antiquities. Many continued on to Naples, where they also viewed Herculaneum and Pompeii, but few ventured far into Southern Italy, and fewer still to Greece, then still under Turkish rule.

After the advent of steam-powered transportation around 1825, the Grand Tour custom continued, but it was of a qualitative difference — cheaper to undertake, safer, easier, open to anyone. During much of the 19th century, most educated young men of privilege undertook the Grand Tour. Germany and Switzerland came to be included in a more broadly defined circuit. Later, it became fashionable for young women as well; a trip to Italy, with a spinster aunt as chaperone, was part of the upper-class women's education, as in E. M. Forster's novel A Room with a View.

Typical itinerary

The itinerary of the Grand Tour was not set in stone, but was subject to innumerable variations, depending on an individual's interests and finances, though Paris and Rome were popular destinations for most English tourists.

The most common itinerary of the Grand Tour shifted across generations, but the British tourist usually began in Dover, England, and crossed the English Channel to Ostend in Belgium, or to Calais or Le Havre in France. From there the tourist, usually accompanied by a tutor (known colloquially as a "bear-leader") and (if wealthy enough) a troop of servants, could rent or acquire a coach (which could be resold in any city – as in Giacomo Casanova's travels – or disassembled and packed across the Alps), or he could opt to make the trip by riverboat as far as the Alps, either travelling up the Seine to Paris, or up the Rhine to Basel.

Upon hiring a French-speaking guide, as French was the dominant language of the elite in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries, the tourist and his entourage would travel to Paris. There the traveller might undertake lessons in French, dancing, fencing, and riding. The appeal of Paris lay in the sophisticated language and manners of French high society, including courtly behaviour and fashion. This served to polish the young man's manners in preparation for a leadership position at home, often in government or diplomacy.

From Paris the traveller would typically sojourn in urban Switzerland, often in Geneva (the cradle of the Protestant Reformation) or Lausanne. ("Alpinism" or mountaineering developed later, in the 19th century.) From there the traveller would endure a difficult crossing over the Alps (such as at the Great St Bernard Pass), which required dismantling the carriage and larger luggage. If wealthy enough, he might be carried over the hard terrain by servants.

Once in Italy, the tourist would visit Turin (and sometimes Milan), then might spend a few months in Florence, where there was a considerable Anglo-Italian society accessible to travelling Englishmen "of quality" and where the Tribuna of the Uffizi gallery brought together in one space the monuments of High Renaissance paintings and Roman sculpture. After a side trip to Pisa, the tourist would move on to Padua, Bologna, and Venice. The British idea of Venice as the "locus of decadent Italianate allure" made it an epitome and cultural set piece of the Grand Tour.

From Venice the traveller went to Rome to study the ancient ruins and the masterpieces of painting, sculpture, and architecture of Rome's Medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque periods. Some travellers also visited Naples to study music, and (after the mid-18th century) to appreciate the recently discovered archaeological sites of Herculaneum and Pompeii, and perhaps (for the adventurous) an ascent of Mount Vesuvius. Later in the period, the more adventurous, especially if provided with a yacht, might attempt Sicily to see its archaeological sites, volcanoes and its baroque architecture, Malta or even Greece itself. But Naples – or later Paestum further south – was the usual terminus.

Returning northward, the tourist might recross the Alps to the German-speaking parts of Europe, visiting Innsbruck, Vienna, Dresden, Berlin and Potsdam, with perhaps a period of study at the universities in Munich or Heidelberg. From there, travellers could visit Holland and Flanders (with more gallery-going and art appreciation) before returning across the Channel to England.

See Wikipedia – Grand Tour

Portrait of Douglas, 8th Duke of Hamilton, on his Grand Tour with his physician Dr John Moore and the latter's son John.

A view of Geneva is in the distance where they stayed for two years.

Painted by Jean Preudhomme in 1774.

![Goethe in the Roman Campagna, by Johann Tischbein, 1787.

In late February of 1787, after four months in Rome, Goethe and his friend Tischbein headed south to Naples, where they arrived on February 25.

The road passed "through and over volcanic hills," and it was "with quiet delight" that he saw Vesuvius to his left, "violently emitting smoke," as they made their way to the city.

Goethe's first ascent of Vesuvius was on March 2, 1787.

He made three attempts to ascend it, the second time (on March 6) with Tischbein, who was less intrigued: "As a visual artist, [Tischbein] always deals only with the most beautiful human and animal forms. This fearsome, shapeless heap of things, which keeps consuming itself and declares war on every feeling for beauty, cannot fail to seem quite hideous to him"

The final ascent was on March 20. Goethe describes the canals formed as the lava flows down the mountain, with the molten material stiffening.

On March 11, Goethe visited Pompeii, where he was taken with the small, cramped space of the town, with even the official buildings reminding him of doll houses. The paintings still to be seen on the walls pleased him, showing as they did "that a whole nation had a delight in art and pictures."](Miscellaneous_files/image007.jpg)

Goethe

in the Roman Campagna, by Johann Tischbein,

1787.

In late February of 1787, after four months in Rome, Goethe and his friend Tischbein headed south to Naples, where they arrived on February 25.

The road passed "through and over volcanic hills," and it was "with quiet delight" that he saw Vesuvius to his left, "violently emitting smoke," as they made their way to the city.

Goethe's first ascent of Vesuvius was on March 2, 1787.

He made three attempts to ascend it, the second time (on March 6) with Tischbein, who was less intrigued: "As a visual artist, [Tischbein] always deals only with the most beautiful human and animal forms. This fearsome, shapeless heap of things, which keeps consuming itself and declares war on every feeling for beauty, cannot fail to seem quite hideous to him"

The final ascent was on March 20. Goethe describes the canals formed as the lava flows down the mountain, with the molten material stiffening.

On March 11, Goethe visited Pompeii, where he was taken with the small, cramped space of the town, with even the official buildings reminding him of doll houses. The paintings still to be seen on the walls pleased him, showing as they did "that a whole nation had a delight in art and pictures."

![VIII.4.4 Pompeii. 1869 illustration from Mark Twain’s 1867 visit to Pompeii. Looking south from tablinum across peristyle into the exedra on the far side.

In 1867 immediately following the American Civil War U.S. author and humourist Mark Twain undertook a decidedly modest yet greatly aspiring "grand tour" of Europe, the Middle East, and the Holy Land, which he chronicled in his highly popular satire The Innocents Abroad.

Not only was it the best-selling of Twain's works during his lifetime, it became one of the best-selling travel books of all time.

Twain in his chapter on Pompeii [XXXI] says "It was a quaint and curious pastime, wandering through this old silent city of the dead—lounging through utterly deserted streets where thousands and thousands of human beings once bought and sold, and walked and rode, and made the place resound with the noise and confusion of traffic and pleasure. They were not lazy. They hurried in those days. We had evidence of that. There was a temple on one corner, and it was a shorter cut to go between the columns of that temple from one street to the other than to go around—and behold that pathway had been worn deep into the heavy flagstone floor of the building by generations of time-saving feet! They would not go around when it was quicker to go through. We do that way in our cities."

See Twain, M., 1869. The Innocents Abroad. San Francisco: Bancroft, Ch. XXXI.](Miscellaneous_files/image008.jpg)

VIII.4.4 Pompeii. 1869 illustration from Mark Twain’s 1867 visit to Pompeii. Looking south from tablinum across peristyle into the exedra on the far side.

In 1867 immediately following the American Civil War U.S. author and humourist Mark Twain undertook a decidedly modest yet greatly aspiring "grand tour" of Europe, the Middle East, and the Holy Land, which he chronicled in his highly popular satire The Innocents Abroad.

Not only was it the best-selling of Twain's works during his lifetime, it became one of the best-selling travel books of all time.

Twain in his chapter on Pompeii [XXXI] says "It was a quaint and curious pastime, wandering through this old silent city of the dead—lounging through utterly deserted streets where thousands and thousands of human beings once bought and sold, and walked and rode, and made the place resound with the noise and confusion of traffic and pleasure. They were not lazy. They hurried in those days. We had evidence of that. There was a temple on one corner, and it was a shorter cut to go between the columns of that temple from one street to the other than to go around—and behold that pathway had been worn deep into the heavy flagstone floor of the building by generations of time-saving feet! They would not go around when it was quicker to go through. We do that way in our cities."

See Twain, M., 1869. The Innocents Abroad. San Francisco: Bancroft, Ch. XXXI.

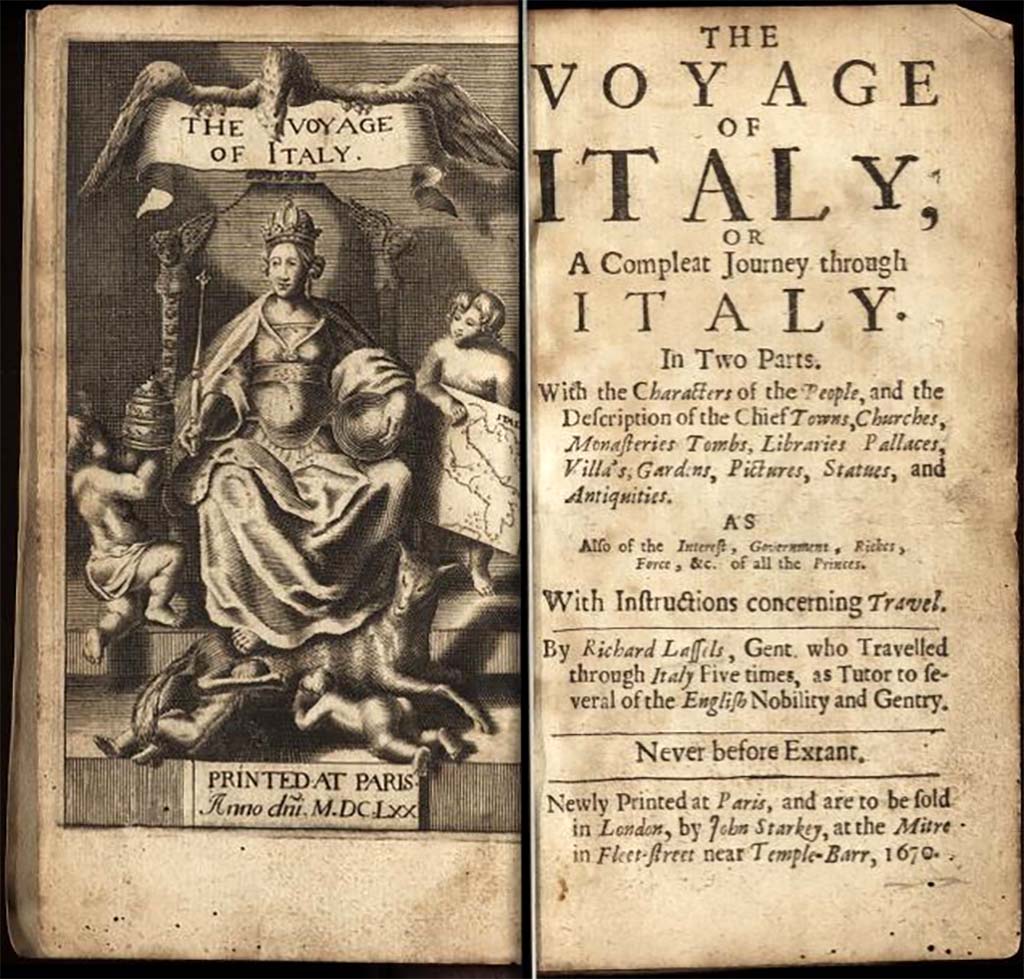

Bronze Foundries

Fonderia

Sommer

1893 advert by Giorgio Sommer.

Sommer was born in Frankfurt am

Main September 2, 1834. He was interested in photography very young, and in

1853 devoted himself to becoming a professional after completing an

apprenticeship at the firm of photographic technique Andreas & Sons in

Frankfurt.

By the end of 1857 he went from Rome to Naples, then still ruled by Ferdinand

II of Bourbon, and opened a studio at 168 Via di Chiaia and then, in about

1860, at 4 Via Monte di Dio, with stock at 5 Via Santa Caterina and at 8 Via

Monte di Dio.

In 1856 moved his business to Naples and later formed a partnership with fellow German photographer Edmund Behles (also known as Edmondo Behles), who owned a studio in Rome.

Operating from their respective Naples and Rome studios, Sommer and Behles became one of the largest and most prolific photography concerns in Italy.

Each photographer had independent careers and studios prior to and following the partnership which began in 1867 and was dissolved in 1874.

In 1872 Sommer bought property

in Piazza Vittoria, corner of Via della Vittoria, in the new district of Chiaia,

where between 1873 and 1874 he moved with his family and opened a new studio

and shop.

On 21 January 1889, when his

son Edmund had already nine years of experience in his father business, the

trading company was registered "Giorgio Sommer e Figlio".

Sommer died in Naples, August 7, 1914.

In addition to photography, he also produced

bronze, marble, silver and terracotta replicas of items in Italian museums and

the excavations.

Some of these copies were used to replace the originals in Pompeii that had been taken to the museum or storage.

Sommer also traded artistic bronzes listed in special catalogues or in a section of his photographic catalogues.

In 1885 he obtained a prize at the Nuremberg's exhibition, for reproductions of ancient bronzes.

In his catalogue of 1914, Catalogue illustré‚ des Bronzes et des Marbres de

la Fonderie Artistique en Bronze,

reproductions are offered in either a marble or plaster or bronze or silver

with a choice of three colours of patina.

V.1.7 Pompeii. 1959. North side of impluvium in atrium with copy of bronze bull, cast by Sommer, in situ.

Photo by Stanley A. Jashemski.

Source: The Wilhelmina and Stanley A. Jashemski archive in the University of Maryland Library, Special Collections (See collection page) and made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial License v.4. See Licence and use details.

J59f0434

V.1.7 Pompeii. December 2007. Room 1, atrium. Pedestal on impluvium where a replica of the bronze bull, made by Sommer to replace the original, stood.

Plaque with name of Giorgio E. Sommer of Piazza Vittoria 6 bis NAPOLI records this.

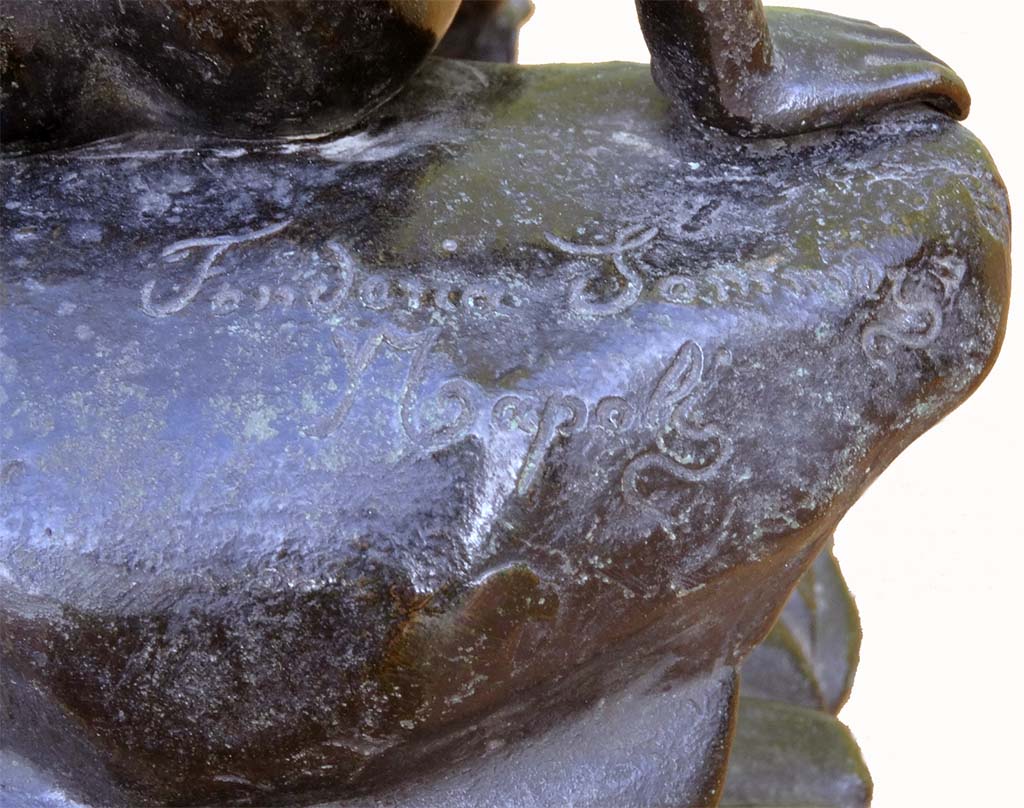

Signature on bronze statue c. 1880. Fonderia Sommer Napoli.

The Neapolitan foundry of Giorgio Sommer produced high quality bronzes and souvenirs, of classical subjects, to appeal to the wealthy Grand Tourists visiting the classical sites of Italy.

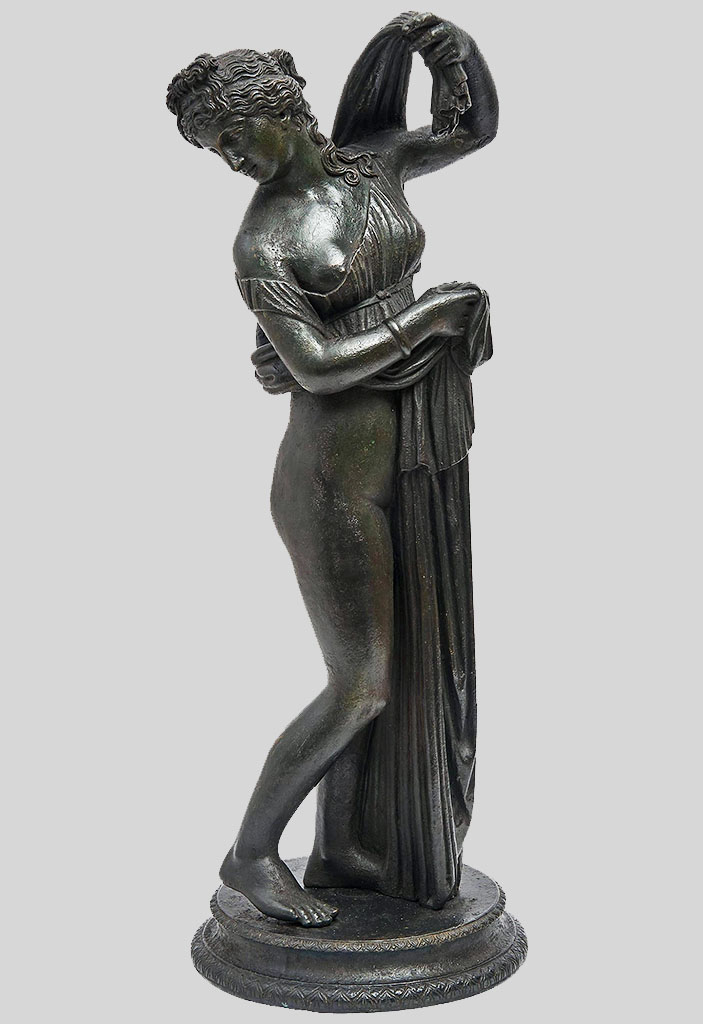

Bronze copy of Venus Callipyge for the Grand Tour and tourists by Giorgio Sommer c.1900.

This particular cast bronze is signed Sommer Napoli on the plinth.

Stereoview

253 by M. Leon and J. Levy.

Bronzes de Pompeii et d'Herculanum, Exposition Universelle de 1867, held in Paris between April and October 1867.

Photo courtesy of Rick Bauer.

Fonderia Chiurazzi

The Fonderia Chiurazzi in the Reale Ospizio dell’Albergo dei Poveri in Naples. Early 1900s.

The Fonderia Chiurazzi was established by Gennaro Chiurazzi senior (1840), first apprentice and then worthy follower of Pietro Masulli, the Neapolitan famous sculptor who first conceived and put in practice the idea of copying the ancient works of art in their splendour, drawing his inspiration from Cellini's method. He founded an art school in the Reale Ospizio dell' Albergo dei Poveri (above), situated in Naples, Piazza Carlo III, and through his hard work succeeded in endowing Naples with two permanent galleries for ancient art, the first in the Galleria Principe di Napoli, the second in Piazza dei Martiri. In this way, all art lovers could be able to admire and buy in the splendid galleries copies of the ancient works from Pompei, Ercolano, Rome and all Italian museums.

Federico and Salvatore Chiurazzi continued their father's work in the most important period (1895 - 1939) which lasted until the Second World War. This 'golden' age gave birth to the marble works, the ceramics, the monumental foundry, the traditional foundry and the foundry for the copying of classic works, and registered the highest number of workers, 600 highly skilled people, true artist in their field, who contributed to produce the greatest monumental works for all countries. Among them, the Madonna del Carmine in Cuba, the equestrian group in General Artigas' honour in Montevideo, the works for the Carnegie Library College in Pittsburg, the Politeama Garibald's quadriga in Palermo, the Vittoriale's quadriga in Rome, the Viscount Caijru's monument in Bahia, the group "Civilisation and Science " in Panama, the Diaz's equestrian group in Naples.

The great development of the monumental foundry did not stop the primary and traditional activity of copying the classic works, which, instead, spread all over the world thanks to the demands coming from both private collectors and lovers and many Museums, such as those in London, Edinburgh, Cambridge, Aberdeen, Glasgow, Dublin, Cardiff, New York, St. Louis, Brooklyn, Boston, Baltimore, Chicago, Pittsburgh, Kansas City, San Francisco and many other interested in showing in their galleries the copies of the masterpieces guarded in Museums. These reproductions' high quality and perfect fidelity, which were possible thanks to the prestigious work of artists who had been trained at the Chiurazzi's artisan school, brought to the continuous flow of demands from abroad. Only the crisis which the war caused in 1939 put an end to the splendour of that extraordinary period, which would have definitely lasted in a peaceful and harmonious world.

Federico's son, Gennaro Chiurazzi junior (1987), grown up in the others' shadow and matured during the best period found himself alone, at nearly 50 years old, in the very hard moment of the recovery, after the tragedy which had shocked the whole world.

The classic works' traditional foundry continued thanks to the unchanged seriousness and love for art of the third generation of workers.

To the Fonderia Chiurazzi belongs an exclusive gallery of plaster casts, a very famous and important collection of plugged plaster moulds produced copying the originals guarded in various Italian museums, from the statues in the Museo Nazionale in Naples to the statues in the Museo Vaticano, Museo Capitolino, Museo di Villa Borghese in Rome, to name the most famous. Chiurazzi's gallery of plaster casts forms an extraordinary heritage which is absolutely necessary for the bronze reproducing of classic and modern works' exact copies, especially from the best 19th-century Neapolitan sculpture. This patrimony, the result of a 100-year work for the firm, is really exclusive and unique in the whole world, as today no authorisation at all is given from the competent Authorities for the bronze reproducing of the works exhibited in the various Italian museums.

Therefore, the only exact, perfectly refined reproductions of the classic and modern sculpture patrimony can be produced only at Fonderia Chiurazzi, thanks to its annexed gallery of plaster casts. At this regard, it can be mentioned the provision for the "J. Paul Getty Museum" in Malibu in California in 1974-'75, which ordered all bronze and marble copies of the originals guarded in Museo Archeologico Nazionale in Naples to furnish its galleries.

(Dr Carmela Iaccarino)

Courtesy of Luigi Setaro, Chiurazzi

Internazionale srl.

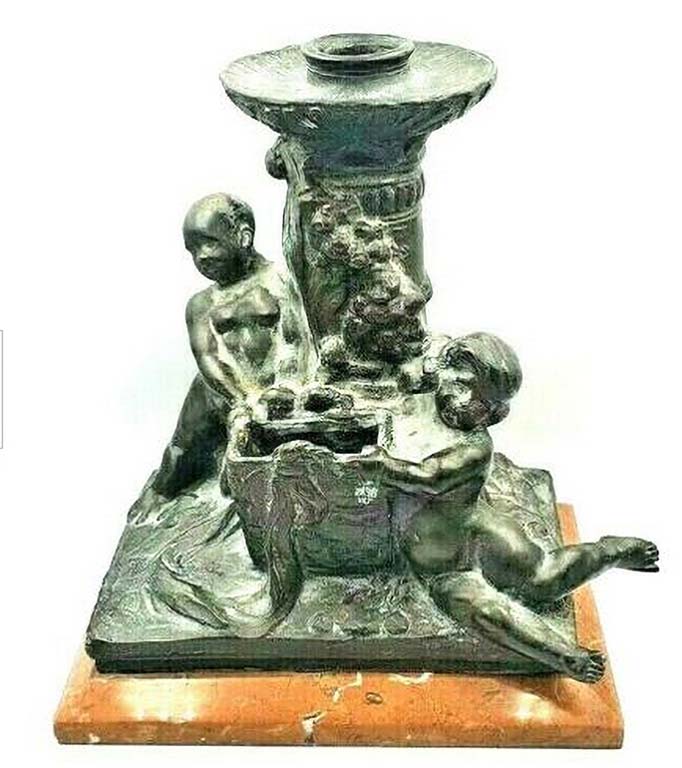

Copy by J. Chiurazzi & Fils of the dancing faun from VI.12.2, the original of which is now in Naples Museum.

The base has a round stamp of Chiurazzi Napoli.

V.1.26 Pompeii. 1964. Room 1, atrium. Reproduction by J. Chiurazzi & Fils of bronze and marble herm bust with wording –

Genio L nostri Felix

L.

(To the genius of our Lucius, Felix the freedman (erects)).

Photo by Stanley A. Jashemski.

Source: The Wilhelmina and Stanley A. Jashemski archive in the University of Maryland Library, Special Collections (See collection page) and made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial License v.4. See Licence and use details.

J64f1536

![J. Chiurazzi & Fils shop and showroom. C.1900. Galleria Principe di Napoli in Naples.

This was a prime location [opposite the Naples Museum] for enticing the museum’s visitors, who, having just seen the museum’s spectacular collections, might want to take home a copy of their own.

J. Chiurazzi & Fils created reproductions of ancient works in media like bronze, terracotta, and marble based on moulds made from the original works housed in Naples’ archaeological museum.

They were well-known for the excellent quality of their work.

See University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology’s Wanamaker Bronze Collection](Miscellaneous_files/image020.jpg)

J.

Chiurazzi & Fils shop and showroom. C.1900. Galleria Principe di Napoli in

Naples.

This was a prime location [opposite the Naples Museum] for enticing the museum’s visitors, who, having just seen the museum’s spectacular collections, might want to take home a copy of their own.

J. Chiurazzi & Fils created reproductions of ancient works in media like bronze, terracotta, and marble based on moulds made from the original works housed in Naples’ archaeological museum.

They were well-known for the excellent quality of their work.

See University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology’s Wanamaker Bronze Collection

Fonderia Artistica Sabatino de Angelis & Fils

Sabatino de Angelis and Salvatore Errico exhibited in The London Exhibition in 1888.

Both were awarded a Diploma of Honour.

VI.8.22 Pompeii. Late 19th century copy of Cupid with Dolphin made by Sabatino de Angelis & Son.

Fonderia Artistica Sabatino de Angelis & Fils Napoli is recorded on the base. The foundry was active in Naples from 1840–1915.

'Cupid with Dolphin' was cast by Sabatino de Angelis & Son, Naples, which obtained permission to manufacture casts from the collections of the Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples in 1888.

The source is a two foot high bronze fountain figure from the House of the Large Fountain, excavated at Pompeii in 1880. It can be dated 1888–1898.

The National Trust at Dorneywood House and Gardens, Buckinghamshire, UK has two bronze sculptures of cupids, signed SAB DE ANGELIS and FILS - NAPLES and dated 1907, one carrying a duck and one with a dolphin, on circular bases.

https://www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/object/1507643

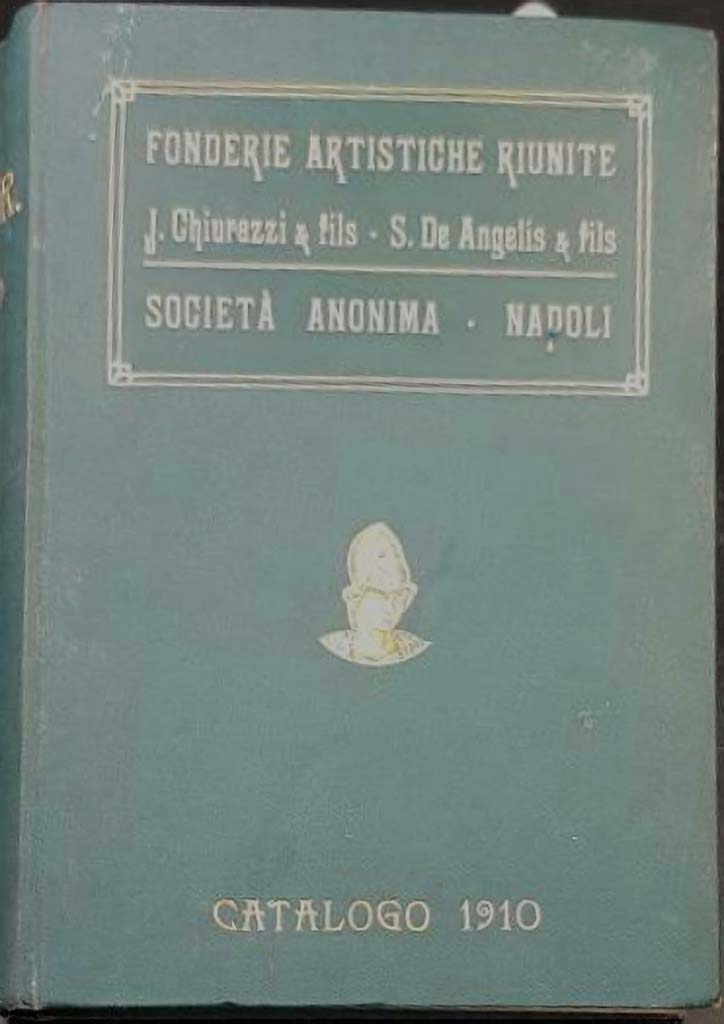

Fonderie Artistiche Riunite J. Chiurazzi & fils – S. De Angelis & fils Catalogo 1910 front cover.

Karl Baedeker, in his widely read guidebook to Southern Italy of 1896, singled out the De Angelis and Chiurazzi foundries as the best producers in Naples of copies of ancient bronzes.

In 1910 the two foundries merged into the Fonderie Artistiche Riunite and offered a wide range of reproductions, from ancient statues to Renaissance and Baroque works.

For the majority of the reproductions, customers could choose among three patinas, ‘Pompéi’, ‘Herculaneum’, or ‘Moderne’, respectively, green, dark brown, and light brown.

By 1915, De Angelis & fils ceased to exist, having been taken over by the Fonderia Chiurazzi, which continued to produce artistic bronze sculpture, both reproductions and original works, under the name of Chiurazzi Internazionale.

See Ostrow, S. F., 2017. Pietro Tacca’s Fontane dei Mostri Marini: Collecting copies at the end of the Gilded Age. Journal of the History of Collections, p. 13-14.

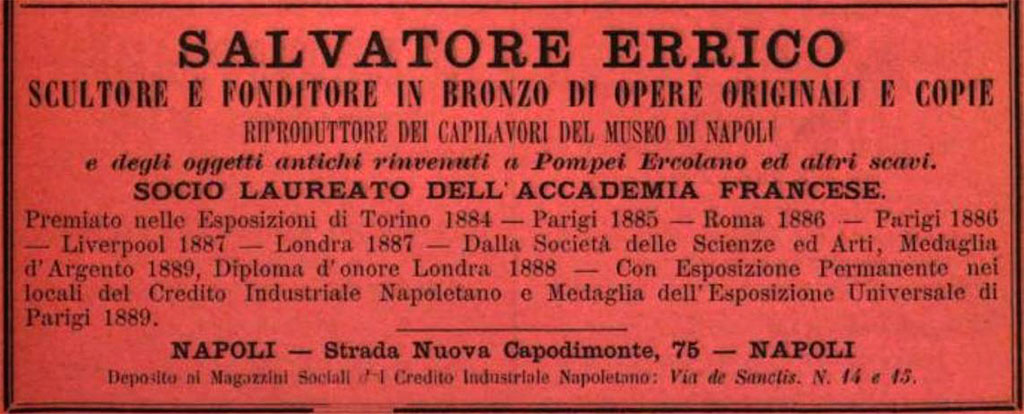

Salvatore Errico, Scultore e

Fonditore

1893 advert in Annuario d'Italia,

Calendario Generale del Regno by Naples sculptor Salvatore Errico

(1848-1934).

Baedeker in his 1912 guide says "Good bronzes are executed also by Salvatore Errico".

Salvatore Errico and Sabatino de Angelis exhibited in The London Exhibition in 1888.

Both were awarded a Diploma of Honour.

He was a decorative sculptor in Naples who also established an antiques business there and was succeeded in both areas of activity by his son Umberto (1884–1945). The latter’s son Gustavo (1910–84) was solely an antiques dealer, with succession to his son Umberto (1948–2017): today the firm trades as ‘Antichità Errico’ under his son Gustavo (b. 1979). It also offers consolidation and restoration, recovery and enhancement of monumental, artistic and archaeological heritage.

Bronze female sculpture by Salvatore Errico (Napoli 1848-1934). Signed "S. Errico Naples".

Fonderia Artistica Laganà

Bronze candlestick. Early 20th century. It has the signature of Gaetano Geraci and the stamp of the Fonderia Artistica Laganà Napoli.

The Fonderia Artistica Laganà, one of the most important foundries in Naples, was founded in 1890 by Giovanni Amedeo Laganà, a patron and collector of art, who gathered around him the best specialists in wax casting, chiselling and bronze in Naples.

In 1898, the sculptor Giuseppe Renda became its technical director.

In 1907 the foundry was transformed into a joint-stock company and after the war it devoted itself to large monuments.

It was frequented by the best Italian artists, including Vincenzo Gemito, who died there in 1929 as a result of the heat from a casting he was working on.

The foundry continued its activity until more than the middle of the 20th century.

"Cockfight" by Gaetano Geraci. Group in antique bronze on veined marble base. Dated 1917. Fonderia Laganà Napoli.

Fonderia Gemito

Bronze bust by Vincenzo Gemito, signed Gemito Napoli and stamped Fonderia Gemito Napoli.

Gemito was born in Naples in 1852.

His talent became apparent very early, at the age of nine, as an assistant to the sculptor Emanuele Caggiano.

In 1868, at the age of sixteen, he modelled the portrait of Mancini and the Gladiator, later exhibited at the Promotrice di Belle Arti in Naples, which aroused the interest of the Italian King Victor Emmanuel II, who acquired a cast for his collection (Museo di Capodimonte).

The "Pescatorello", which was a great success at the 1877 Salon, dates from 1876.

Between 1877 and 1881 he lived and worked in Paris. Back in Naples, he became increasingly interested in the ancient classics.

In 1883 he founded the Fonderia Gemito, Napoli, producing bronzes using the lost-wax casting method.

He died at the age of seventy-seven in Naples on the first of March 1929.

Late 19th century bronze bust of Marsyas by Vincenzo Gemito, stamped Fonderia Gemito Napoli.

Pompeii,

Hotels, Local Houses, Railways, Etc.

Grand Hotel Suisse

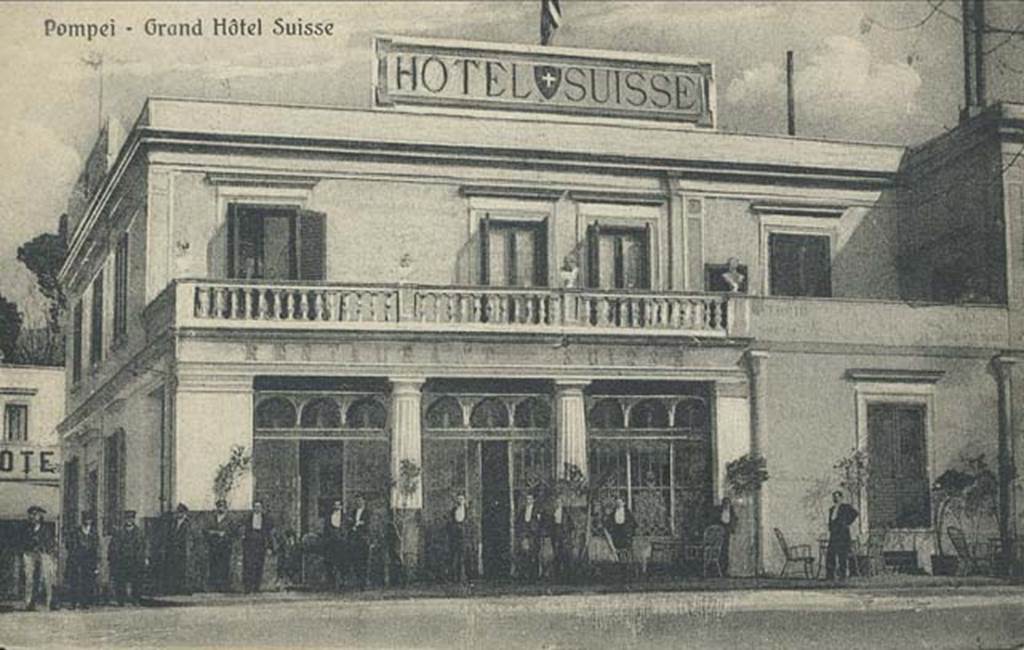

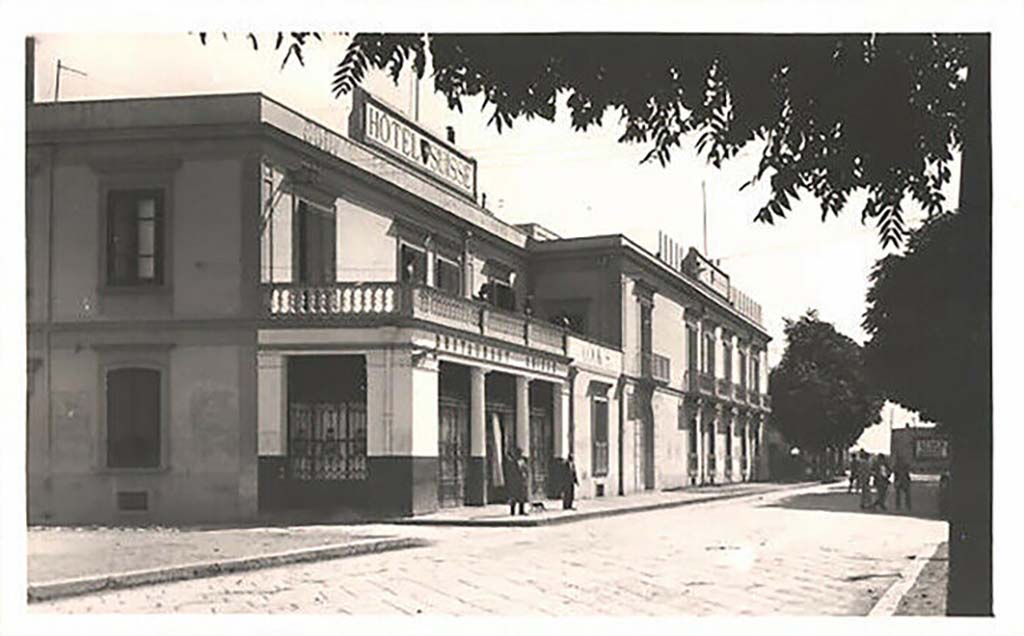

H.1. Grand Hotel Suisse, Pompeii, c.19th century. Hotel near entrance. Photo courtesy of Rick Bauer.

Behind on the left of the photograph is the Hotel Diomede.

H.1a. Grand Hotel Suisse, Pompeii. 1931.

H.1b. Grand Hotel Suisse, Pompeii. 19th century? The horse and carriage are where the motor car is in 1924 (below).

H.1c. Pompeii, 2nd February 1924. Photo taken near the ruins of

Pompeii, unspecified location.

The motor car is outside the Hotel Suisse where the

horse and carriage were in the 19th century postcard above.

Photo courtesy of Rick Bauer.

Hotel Diomede e Ristorante Diomede.

H.1d. Detail from postcard c.1916 with title "Ristorante Diomede e Hotel Suisse" with view of Hotel Diomede and Hotel Suisse.

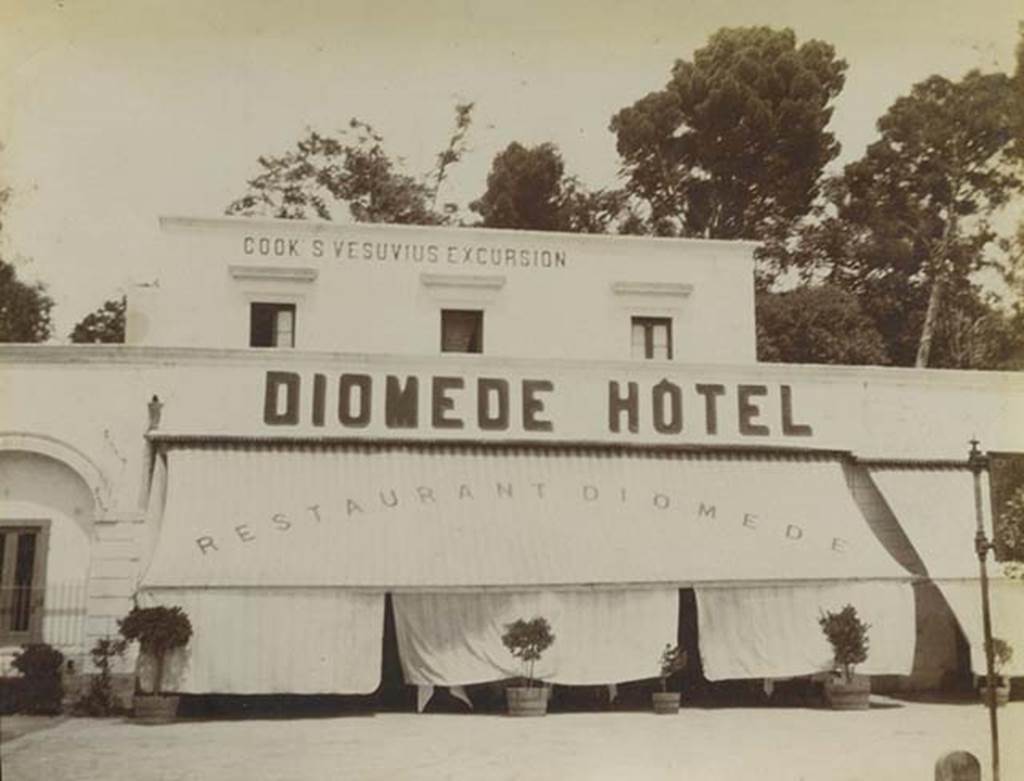

H.2. Diomede Hotel, Pompeii. 1905. Hotel near entrance. Photo courtesy of Rick Bauer.

The Diomede, which can be considered the oldest hotel in Pompeii, began its activity in 1840 from the transformation of the ancient "Taverna del Lapillo." The latter was already in operation when in April 1748, King Charles of Bourbon (1716 -1788) began excavations for archaeological research in the locality called Cività belonging to the municipality of Torre Annunziata.

The tavern, in fact, overlooked the provincial road of Calabrie and was a resting place for the coachmen and carters who travelled it every day.

With the continuation of the excavations it began to be frequented also by the workers involved in the excavation and by the first visitors who flocked to the place to admire and study the remains of the ancient city that was slowly brought to light, so much so that in 1780 the Director of the Excavations Francesco La Vega (1737-1815), in asking King Ferdinand IV (1751-1825) to purchase land in order to continue the excavations, advised him to also buy the Taverna del Lapillo with the adjoining land owned by Giovanni Andrea de Marinis, Marquis of Genzano (which had been given to him by the Piccolomini of Aragon) in order to renovate it and make it a decent place of accommodation and refreshment for visitors.

Later, with royal decree of March 16, 1815, King Joachim Murat (1767-1815) granted ownership of the tavern and all the land outside the ancient walls of Pompeii, subject however to the unloading of the excavated material, to the head of division of the Ministry of the Interior, architect Raffaele Minervini to reward him for the work done on the Royal Bourbon Museum and the Excavations. On the death of Minervini, the tavern was rented to Mr. Francesco Prosperi who, with appropriate expansion works, transformed it into a hotel which was first called Hotel Bellevue and later Hotel Diomede. In 1868 Prosperi bought the place for the sum of 14,025 lire, equal to 3,300 ducats. In 1913, due to a financial failure of the Prosperi heirs, the hotel was put up for auction, becoming the property of the Southern Banking Company which in turn, on 13 July 1922, sold it to Aurelio Item and his wife Giulia Pagano.

The hotel was located in Piazza Porta Marina Inferiore, attached to the post office and occupied the initial part of Via Villa dei Misteri towards the north, a road that leads uphill to Porta Marina Superiore, with the Circumvesuviana station, and further up the Contrada Giuliana, with the famous Villa dei Misteri, formerly Villa Item. It extended beyond the current tollbooth of the Naples-Pompeii motorway. It was precisely to build this motorway section that the Diomede was purchased in the form of expropriation, by the Società Autostrade Meridinali on 27 March 1930, and consequently completely demolished.

Today, however, a solitary volcanic stone niche remains of the ancient tavern and hotel on the road that climbs towards the Pompeii Villa dei Misteri station on the Circumvesuviana, close to the entrance to the Porta Marina excavations.

The English writer Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1803-1877) lived in the Hotel Diomede for a long time whilst writing his novel "The last days of Pompeii".

Legendary are the constant stops in this tavern of the Bourbon legitimist Antonio Cozzolino (1824-1870), known as the "brigante Pilone".

See Amorosi V., La

taverna Diomede in Sylva Mala XVI, Centro Studi Archeologici di Boscoreale,

Boscotrecase e Trecase, p. 8.

Hotel Diomede. A solitary volcanic stone niche is all that remains on the road that climbs towards the Pompeii Villa dei Misteri station on the Circumvesuviana, close to the entrance to the Porta Marina excavations.

See Amorosi V., La

taverna Diomede in Sylva Mala XVI, Centro Studi Archeologici di Boscoreale,

Boscotrecase e Trecase, p. 9.

Hotel Diomede. August 2020. A solitary volcanic stone niche is all that remains on the Via Villa dei Misteri by the entrance/exit to the Napoli-Pompei Autostrada.

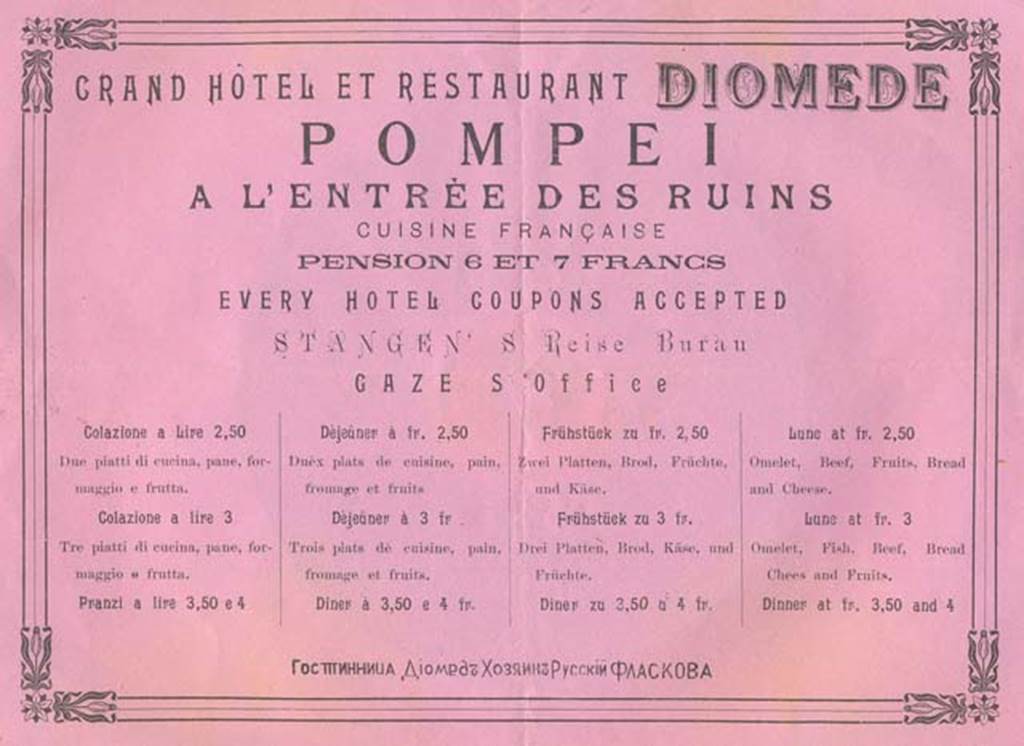

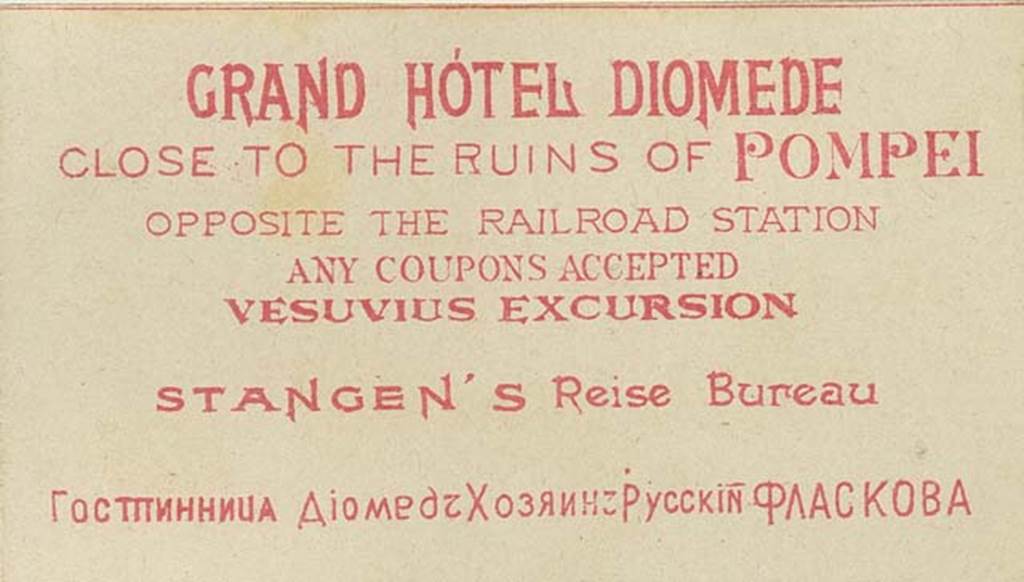

H.3. Diomede Hotel, Pompeii. Advertisement dated c.1900’s. Photo courtesy of Rick Bauer.

H.4. Diomede Hotel, Pompeii. Advertisement dated c.1900’s. Photo courtesy of Rick Bauer.

Taverna del Lapillo or

Rapillo

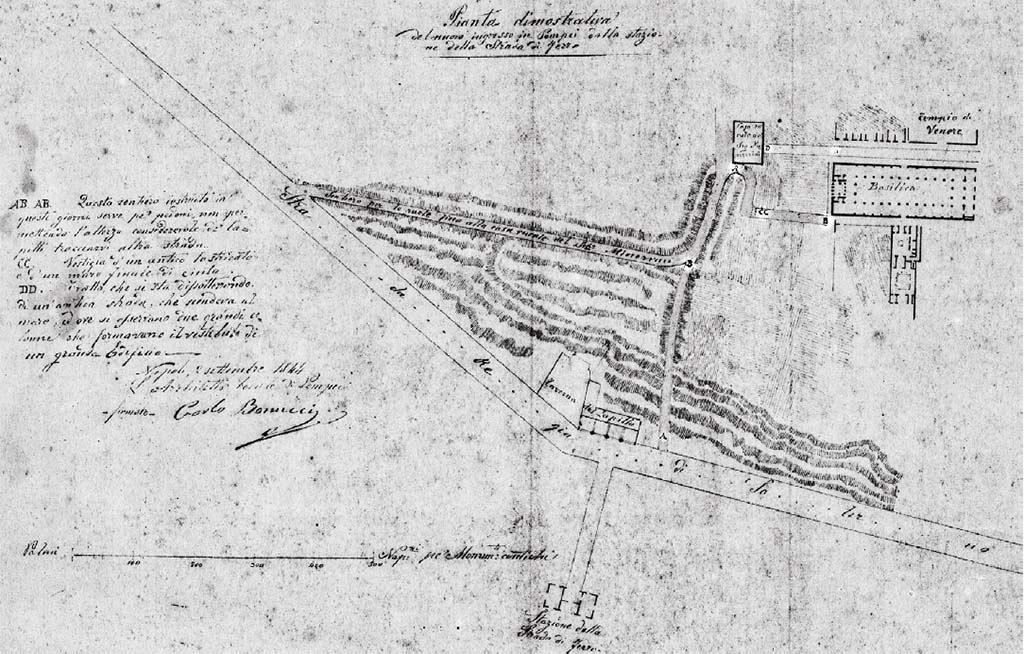

1844 plan. "Pianta

dimostrativa del nuovo ingresso in Pompei dalla stazione della Strada di

Mezzo".

The plan shows

the Taverna del Lapillo on the Strada Regia di Salerno and the casa Rurale del

Sig. Minervini.

The legend says:

AB. AB. Questo

sentiero costruito in questi giorni serve pe’ pedoni, non permettendo l’altezza

considerevole de’ lapilli tracciarvi altra strada.

CC. Vestigia

d’un antico lastricato e d’un muro finale di cinta.

DD. Tratto che

si sta dissotterrando di un’antica strada che scendeva al mare dove si

osservano due grandi colonne che formavano il vestibolo di un grande Edifico.

Napoli 2

settembre 1844. L’Architetto degli scavi di Pompei – firmato – Carlo Bonucci.

Taverna del Rapillo (or Lapillo). 1822 drawing by F. Callet " Inn at the foot of the excavations of Pompeia on the road to Salerno".

Now in the École nationale supérieure des Beaux‑Arts de Paris. Inventory number 3275.

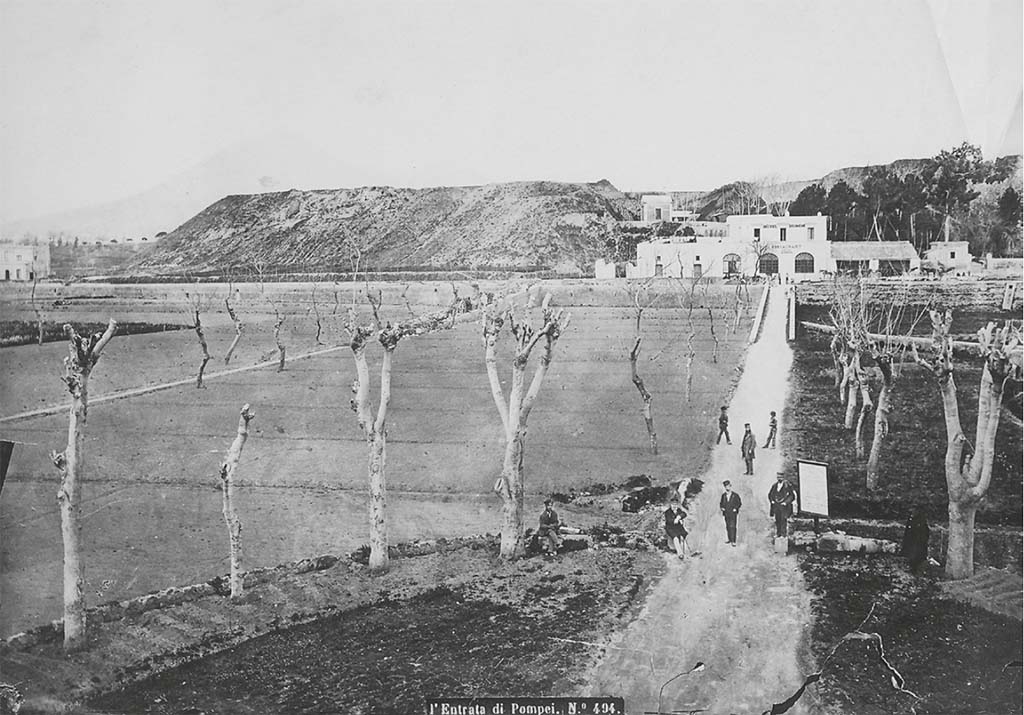

Pre-1889 photo by

Roberto Rive (or Giorgio Sommer?), L' Entrata di Pompei, no. 494.

According to Zanella, this shows the entrance to the Pompeii site from the station. Opposite, the Diomede Hotel, taverna del Rapillo.

On the left, the piles of rubble accumulated since the beginning of the excavation outside the urban perimeter on land that belonged to the Irace family and R. Minervini.

Comparing a drawing by Callet (fig. 27) dated 1822 and a photograph by the Alinari brothers dated 1890 the hotel seems to retain the old configuration of the taverna del Rapillo. In particular, the three front arcades visible the Callet drawing have been preserved from the old tavern. On the other hand, transformations seem to have taken place on the western part of the building where, instead of the open space that can be seen on the older plans, three doors have been pierced in the blind wall visible in the drawing, confirming the widening of the structure shown in later plans. To the east, already at the time of Callet, a barn leans against the factory building. Another building, visible in the photograph of the Alinari brothers, was added later.

See Zanella S., 2019. La caccia fu buona : Pour une histoire des fouilles à Pompéi de Titus à l’Europe. Naples : Centre Jean Bérard, p. 60, fig. 27 and 28.

House near Pompeii entrance

H.5. Pompeii. 1905/6? House near entrance, photo with wording on back as below. Photo courtesy of Rick Bauer.

H.5A. Pompeii. 1905/6? Wording on rear of above photograph “Pompei. House buried in lava – (only upper storey of 3 above present level).”

Photo courtesy of Rick Bauer.

Stazione ferroviaria. Railway

stations.

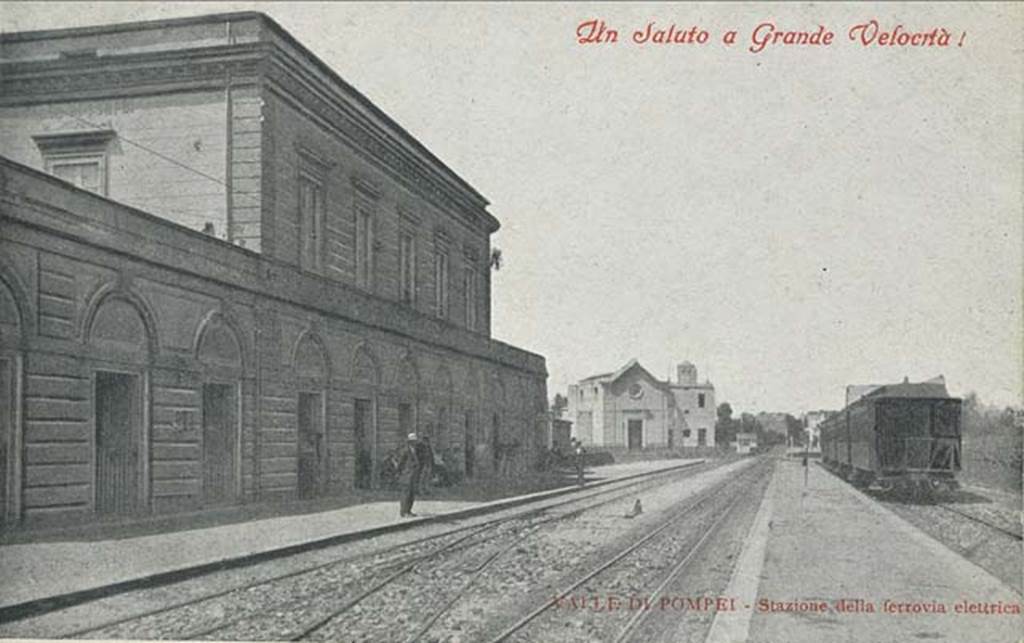

Valle di Pompei Stazione

della ferrovia elettrica

Valle di Pompei Electric railway station

H.6. Valle di Pompei, Stazione della ferrovia elettrica. Undated photo. Courtesy of Rick Bauer.

Vecchia Stazione Pompei

Ferrovia Napoli-Salerno.

Old Pompeii station on

the Naples to Salerno line.

![H.7. 1929 map of Pompeii by Engelmann showing railway station on the Naples to Salerno line.

From the station the road led to the Grand Hotel Suisse, Hotel Quisisana and the Hotel Diomede.

A right turn took you past the post office to the entrance ticket office at the [now] Piazza Porta Marina Inferiore.

Up the steps took you past the statues of Mau and Ruggiero (now in the Lararia dei Pompeianisti next to the antiquarium).

The site was entered via the Porta Marina.

Photo courtesy of Rick Bauer.](Miscellaneous_files/image052.jpg)

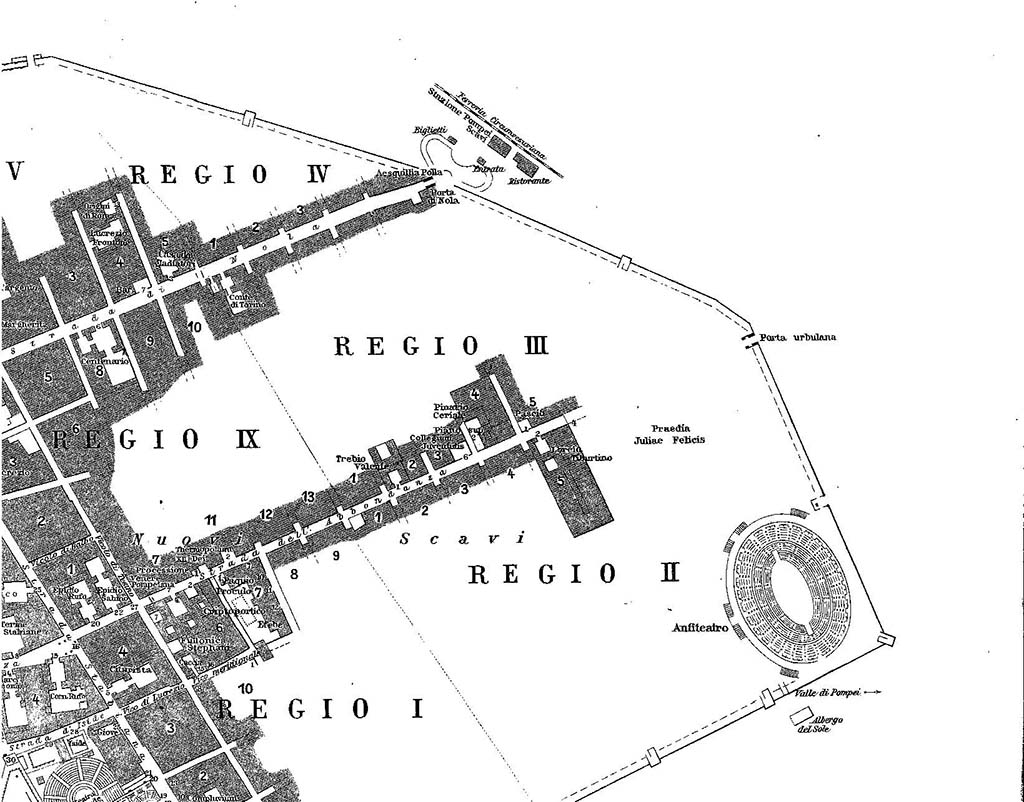

H.7. 1929 map of Pompeii by Engelmann showing railway station on the

Naples to Salerno line.

From the station the road led to the Grand

Hotel Suisse, Hotel Quisisana and the Hotel Diomede.

A right turn took you past the post office to

the entrance ticket office at the [now] Piazza Porta Marina Inferiore.

Up the steps took you past the statues of Mau

and Ruggiero (now in the Lararia dei Pompeianisti next to the antiquarium).

The site was entered via the Porta Marina.

Photo courtesy of Rick Bauer.

H.8.

Disused Pompeii Scavi station on the line from Naples to Salerno. 2010. Photo

courtesy of Rick Bauer.

Mark Twain visited Pompeii in 1867.

In his satirical account he describes leaving Pompeii: We came out from under the solemn mysteries of this city of the Venerable Past—this city which perished, with all its old ways and its quaint old fashions about it, remote centuries ago, when the Disciples were preaching the new religion, which is as old as the hills to us now—and went dreaming among the trees that grow over acres and acres of its still buried streets and squares, till a shrill whistle and the cry of “All aboard—last train for Naples!” woke me up and reminded me that I belonged in the nineteenth century, and was not a dusty mummy, caked with ashes and cinders, eighteen hundred years old. The transition was startling. The idea of a railroad train actually running to old dead Pompeii, and whistling irreverently, and calling for passengers in the most bustling and business-like way, was as strange a thing as one could imagine, and as unpoetical and disagreeable as it was strange.

See Twain M., 1869. The Innocents Abroad or the New Pilgrims Progress. Hartford, CT: American Publishing Co., Chapter XXXI.

Vecchia Circumvesuviana

Pompei Scavi Stazione a Porta di Nola

Old Circumvesuviana Pompei Excavations Station at Porta di Nola

H.9. 1929

map of Pompeii by Engelmann showing old Circumvesuviana Pompei Scavi station,

restaurant, ticket office and entrance through Porta di Nola.

Photo

courtesy of Rick Bauer.

H10. The station was opened with the line in 1904 and was known as Pompei, then Pompei Scavi and then Pompei Valle.

Originally it had a small passenger building with ticket office, from which it was possible to access the area of archaeological excavations through Porta di Nola.

Its isolated position led to poor usage and, after the station building was demolished, traveller movement became almost nil, and it was closed in the early 2000s.

See http://www.lestradeferrate.it/63pompei/63pompeiv.htm

H.11. Old Porta Nola entrance to Pompeii Scavi and old restaurant building. June 2010. Photo courtesy of Rick Bauer.

H.12. Old Porta Nola entrance booth. June 2010. Photo courtesy of Rick Bauer.

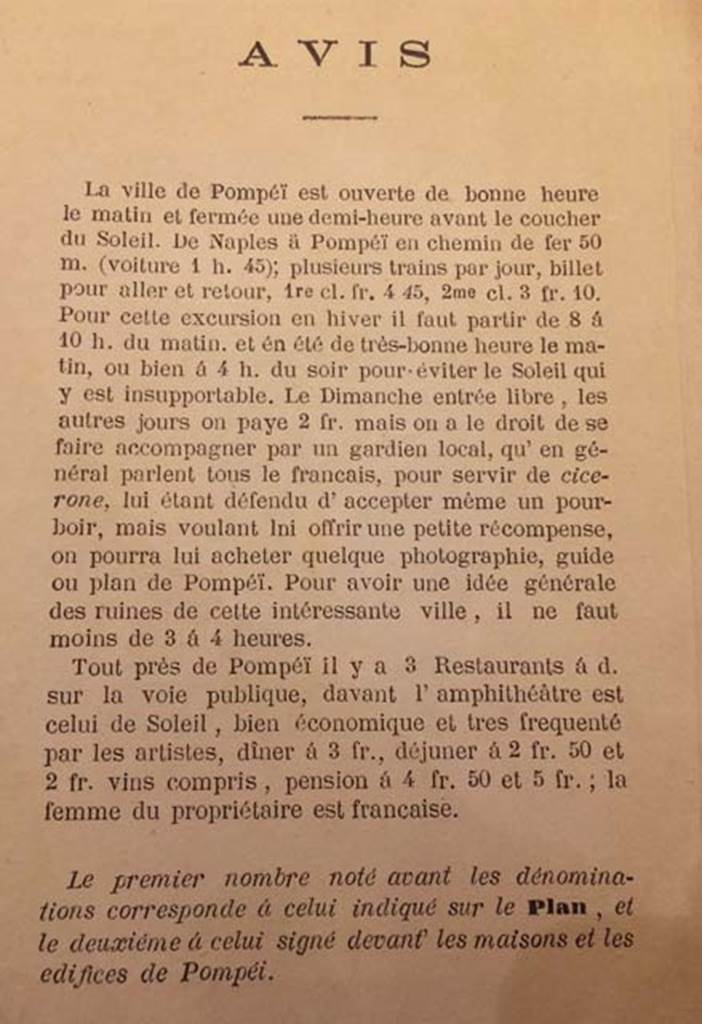

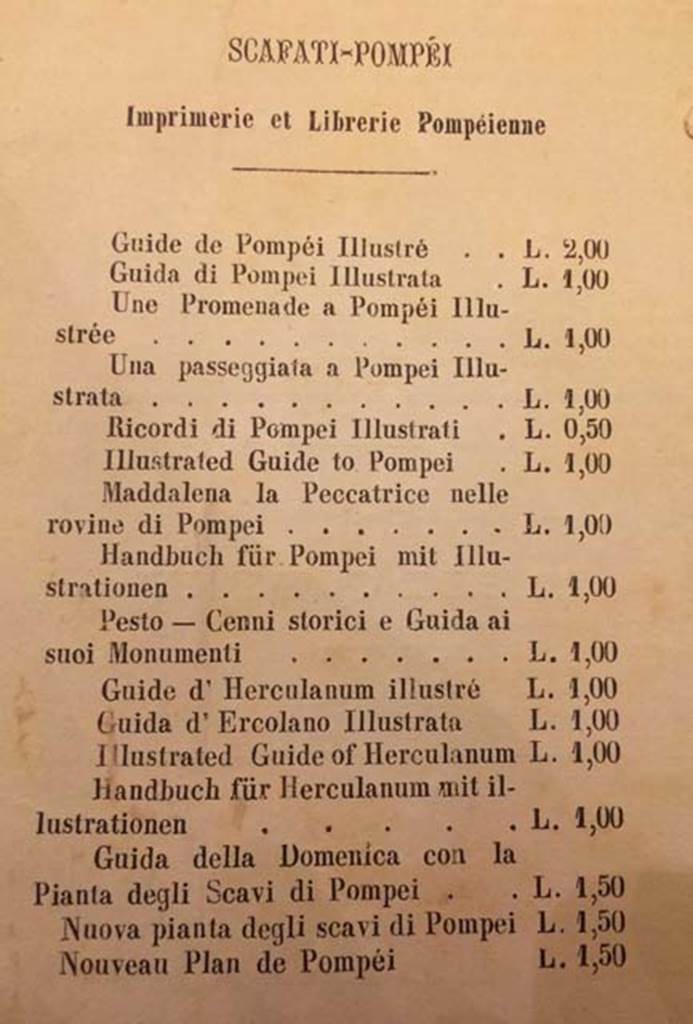

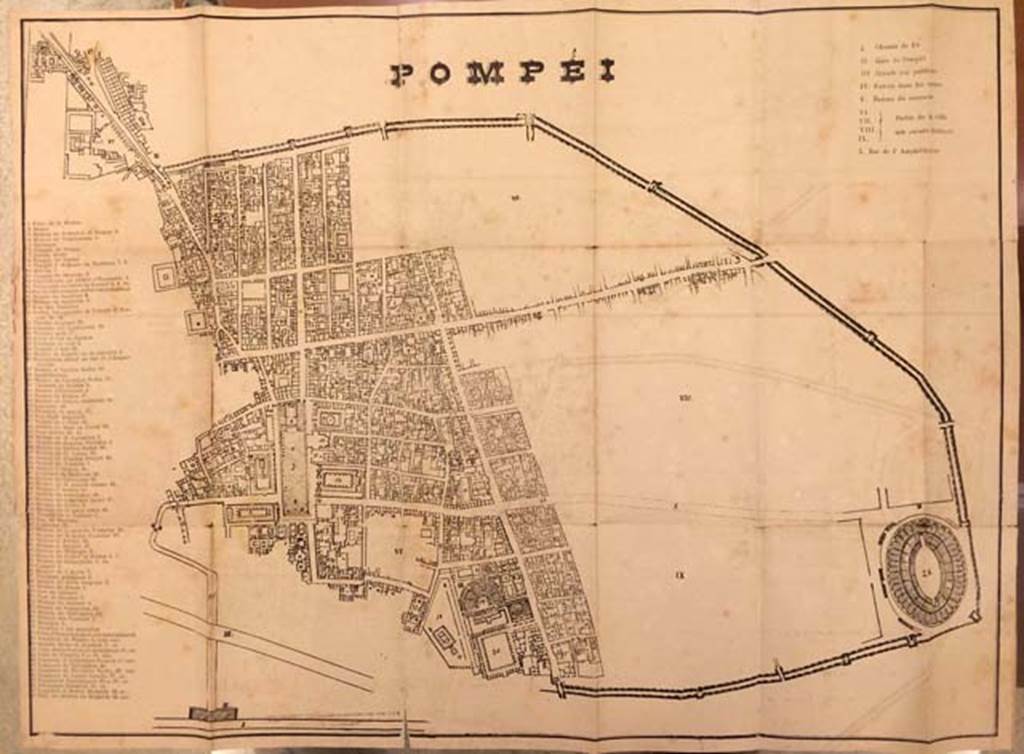

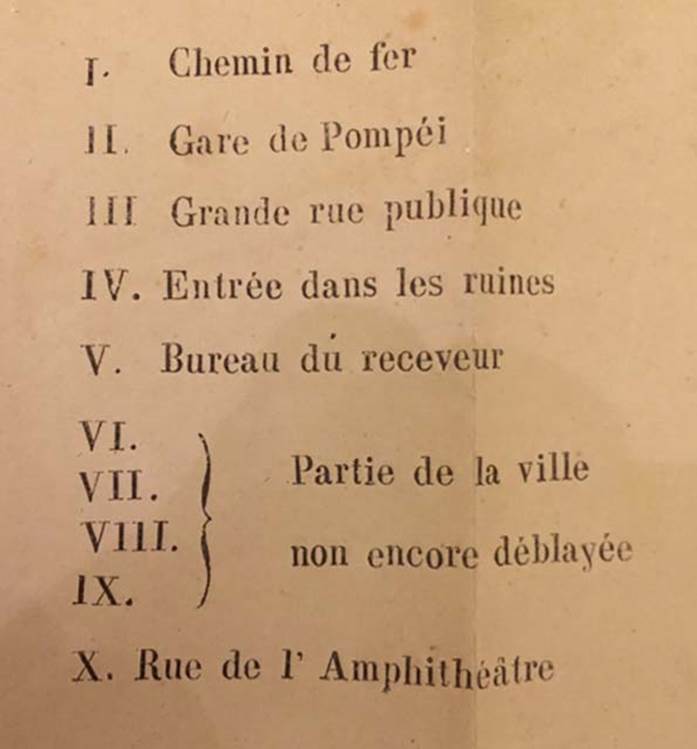

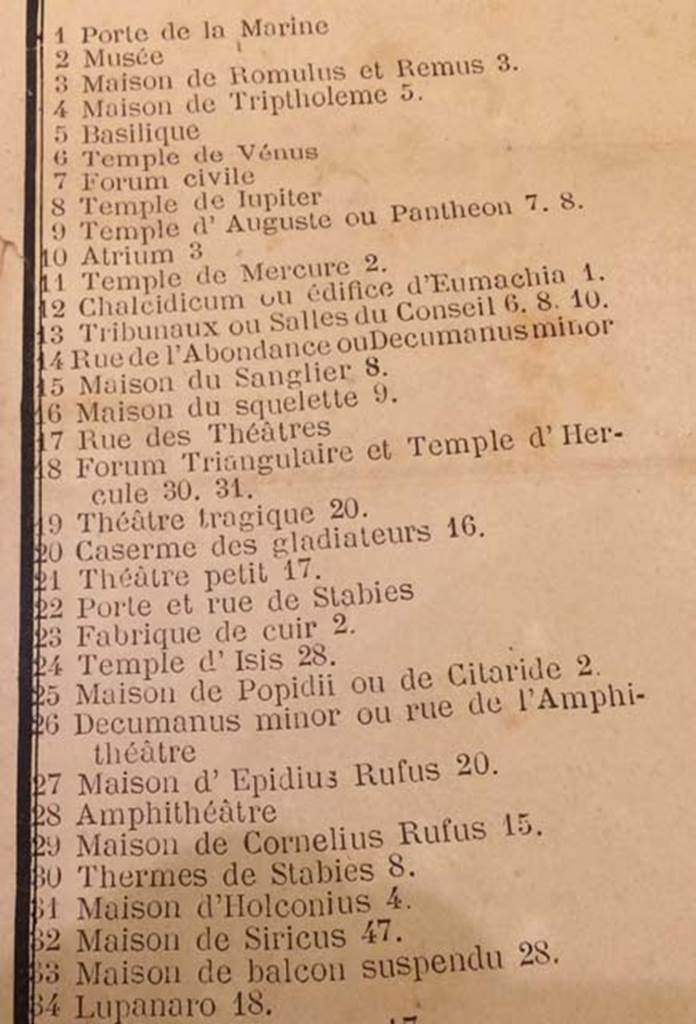

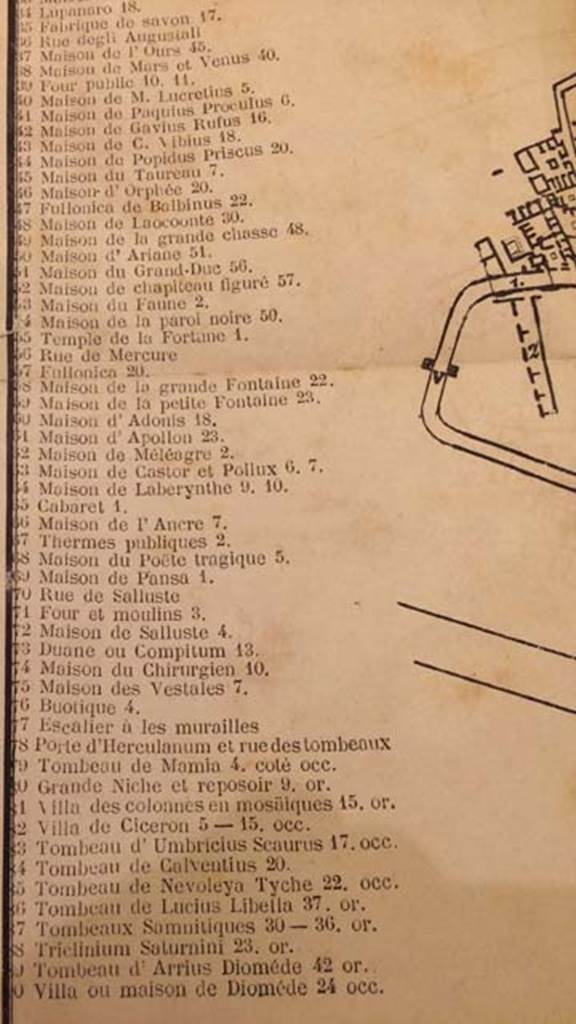

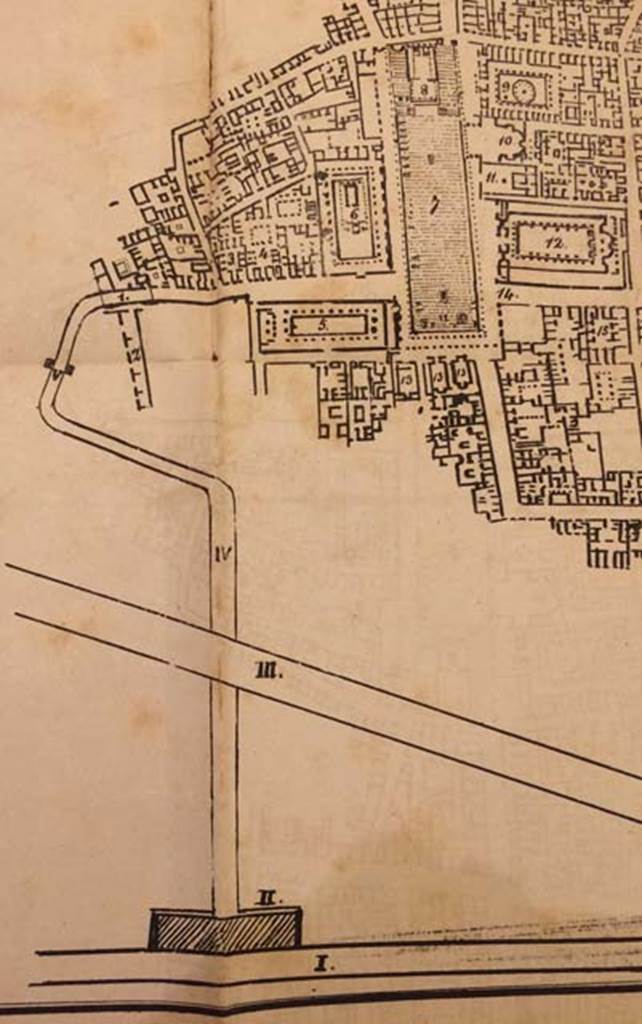

Pompeii

Guide, by Scafati 1876

Pompeii guide by Scafati 1876, cover. Photo courtesy of Rick Bauer.

Pompeii guide by Scafati 1876. Photo courtesy of Rick Bauer.

Pompeii guide by Scafati 1876. Photo courtesy of Rick Bauer.

Pompeii guide by Scafati 1876. Plan. Photo courtesy of Rick Bauer.

Pompeii guide by Scafati 1876. Plan key. Photo courtesy of Rick Bauer.

Pompeii guide by Scafati 1876. Plan key to houses. Photo courtesy of Rick Bauer.

Pompeii guide by Scafati 1876. Plan key to houses. Photo courtesy of Rick Bauer.

Pompeii guide by Scafati 1876. Railway station and entrance. Photo courtesy of Rick Bauer.

Danish Artists The Grand Tour Bronze Foundries Hotels, Local Houses, Railways Pompeii Guides Tickets Mysteries to solve Maledizione – Curse of Pompeii